Visualising the London Underground with Tableau

I’ve always thought of the London Underground as a sort of teleportation system. You enter a portal in one place, and with relatively little effort appeared at a portal in another place. Although in Star Trek our heroes entered a special room and stood well-separated on platforms, rather than packing themselves into metal tubes.

I read Christian Wolmar’s book, The Subterranean Railway about the history of the London Underground a while ago. At the time I wished for a visualisation for the growth of the network since the text description was a bit confusing. Fast forward a few months, and I find myself repeatedly in London wondering at the horror of the rush hour underground. How do I avoid being forced into some sort of human compression experiment?

Both of these questions can be answered with a little judicious visualisation!

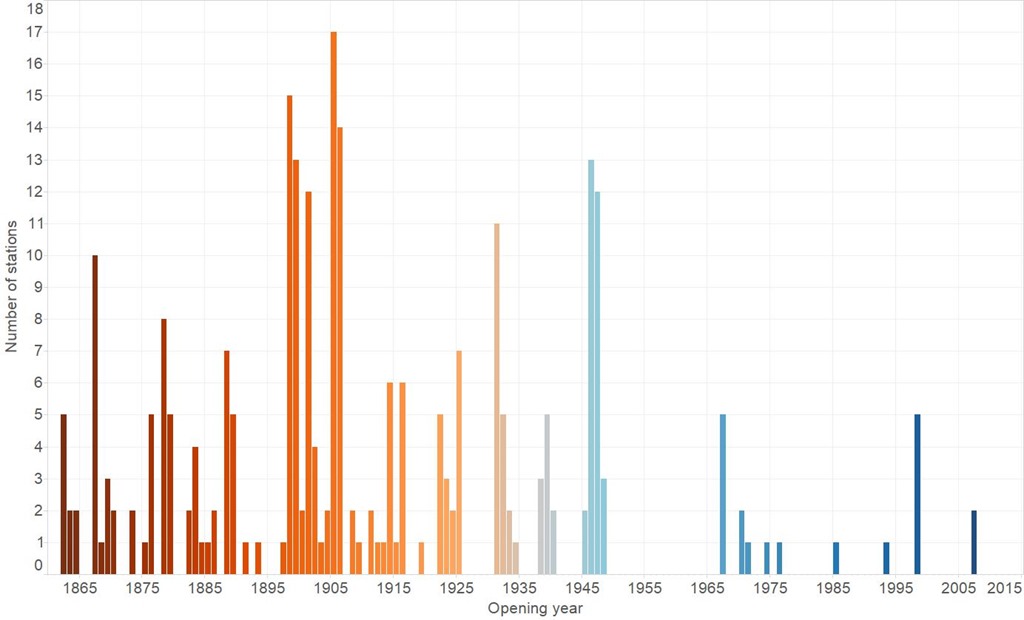

First up, the history question. It turns out that other obsessives have already made a table containing a list of the opening dates for the London Underground. You can find it here, on wikipedia. These sortable tables are a little tricky to scrape, they can be copy-pasted into Excel but random blank rows appear. And the data used to control the sorting of the columns did confuse our Table Xtract tool, until I fixed it – just to solve my little problem! You can see the number of stations opened in each year in the chart below. It all started in 1863, electric trains were introduced in the very final years of the 19th century – leading to a burst of activity. Then things went quiet after the Second World War, when the car came to dominate transport.

Originally I had this chart coloured by underground line but this is rather misleading since the wikipedia table gives the line a station is currently on rather than the one it was originally built for. For example, Stanmore station opened in 1932 as part of the Metropolitan line, it was transferred to the Bakerloo line in 1939 and then to the Jubilee line in 1979. You can see the years in which lines opened here on wikipedia, where it becomes apparent that the name of an underground line is fluid.

So I have my station opening date data. How about station locations? Well, they too are available thanks to the work of folk at Openstreetmap, you can find that data here. Latitude-longitude coordinates are all very well but really we also need the connectivity, and what about Harry Beck’s iconic “circuit diagram” tube map? It turns out both of these issues can be addressed by digitizing station locations from the modern version of Beck’s map. I have to admit this was a slightly laborious process, I used ImageJ to manually extract coordinates.

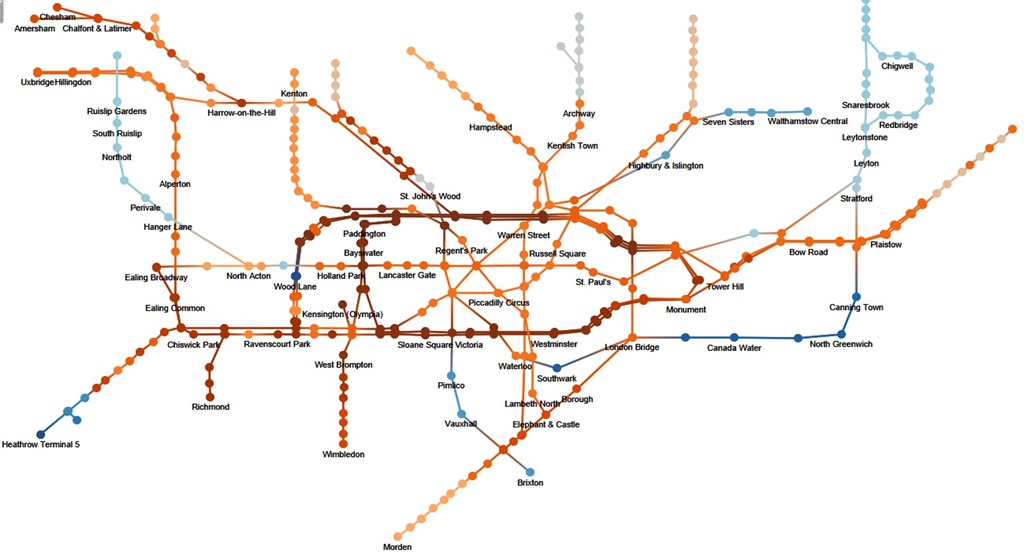

I’ve shown the underground map coloured by the age of stations below.

Deep reds for the oldest stations, on the Metropolitan and District lines built in the second half of the 19th century. Pale blue for middle aged stations, the Central line heading out to Epping and West Ruislip. And finally the most recent stations on the Jubilee line towards Canary Wharf and North Greenwich are a darker blue.

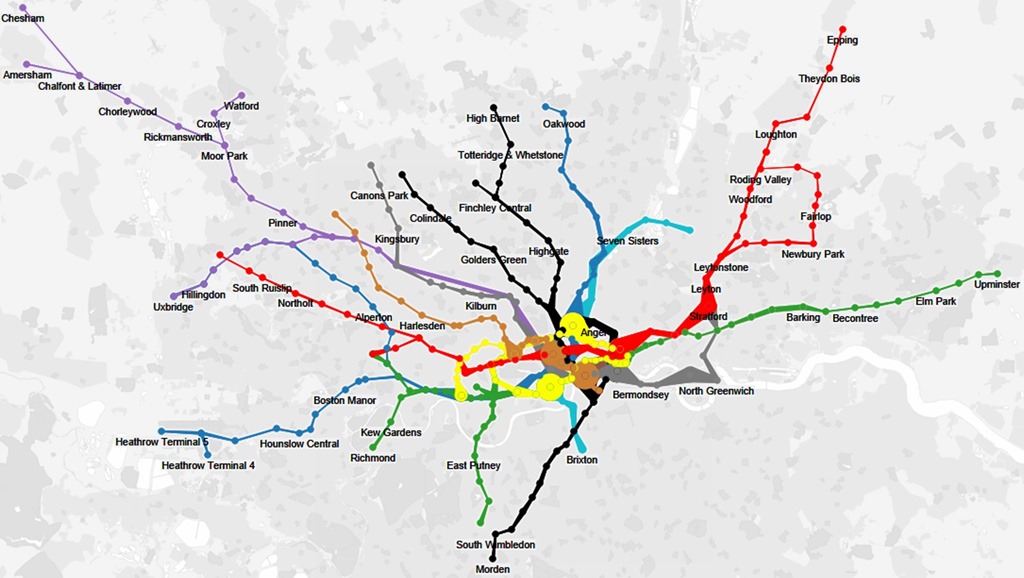

Next up is traffic, or how many people use the underground. The wikipedia page contains information on usage, in terms of millions of passengers per year in 2012 covering both entries and exits. I’ve shown this data below with traffic shown at individual stations by the thickness of the line.

I rather like a “fat lines” presentation of the number of people using a station, the fatter the line at the station the more people going in and out. Of course some stations have multiple lines so get an unfair advantage. Correcting for this it turns out Canary Wharf is the busiest station on the underground, thankfully it’s built for it. Small above ground beneath it is a massive, cathedral-like space.

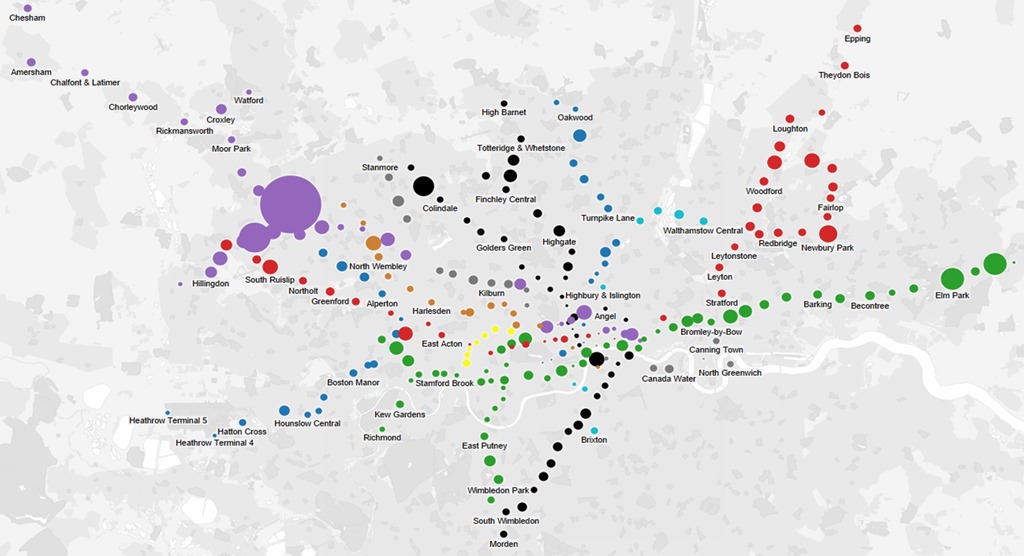

More data is available as a result of a Freedom of Information request (here) which gives data broken down by passenger action (boarding or alighting), underground line, direction of travel and time of day – broken down into fairly coarse chunks of the day. I use this data in the chart below to measure the “commuteriness” of each station. To do this I take the ratio of people boarding trains in the 7am-10am time slot with those boarding 4pm-7pm. For locations with lots of commuters, this will be a big number because lots of people get on the train to go to work in the morning but not many get on the train in the evening, that’s when everyone is getting off the train to go home.

By this measure the top five locations for “commuteriness” are:

- Pinner

- Ruislip Manor

- Elm Park

- Upminster Bridge

- Burnt Oak

It was difficult not to get sidetracked during this project, someone used the Freedom of Information Act to get the depths of all of the underground stations, so obviously I had to include that data too! The deepest underground station is Hampstead, in part because the station itself is at the top of a steep hill.

I’ve made all of this data into a Tableau visualisation which you can play with here. The interactive version shows you details of the stations as your cursor floats over them, allows you to select individual lines and change the data overlaid on the map including the depth and altitude data that.